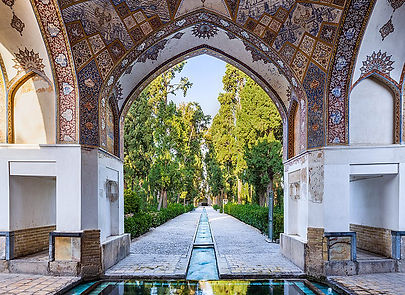

Bagh-e Fin, Kashan

c. 1590 CE, Safavid Iran

Thinking through Alfred Gell (1945-1997)’s “Art and Agency” & “Technology of Enchantment”

Bagh-e Fin is the Safavid crown jewel of Persian garden craft: a walled rectangle where cypress allées, turquoise pools, and gurgling qanat water channels conjure a living cosmogram of kingship and paradise. Through Alfred Gell’s lens, the garden is not a visual backdrop but an active agent—a hydraulic, vegetal, and architectural mechanism that does political and metaphysical work.

Indexical water-magic

Gell stresses that an artwork’s power lies in its capacity to enchant via hidden technique. At Fin, the marvel is the qanat: an underground aqueduct that taps a distant mountain spring, delivering water that emerges in crystal-clear fountains without mechanical pumps. Visitors, unaware of the subterranean labor, experience the pools as effortless abundance—an index of sovereign mastery over nature and, by extension, cosmic order.

Distributed personhood of the Shah

Every jet of water, every shade cast by towering cypress, extends the Shah’s intentionality. Like Gell’s Polynesian canoe prowboards that “stand in” for their owners, Bagh-e Fin externalizes Safavid charisma. The garden’s fourfold geometry (char-bagh) mirrors the Quranic rivers of paradise; its axial pavilion, framed by archways of muqarnas stalactites, spatializes the throne as the navel of the world. The ruler may be absent, yet his agency circulates continuously through water, symmetry, and scent.

Enchantment through sensory choreography

Gell’s “technology of enchantment” functions here via multisensory layering: cool air wafts from water channels, rose and sour-orange blossoms perfume the breeze, and the gentle splash of fountains creates a rhythmic auditory veil that dampens worldly noise. These stimuli are carefully orchestrated to lull visitors into a contemplative trance where political loyalty, spiritual awe, and sensual pleasure fuse.

Temporal palimpsest

Bagh-e Fin also exemplifies Gell’s notion of time-binding objects. Safavid inscriptions, Qajar renovations, and modern nationalist memories (e.g., the assassination of reformer Amir Kabir in the bathhouse) coexist, turning the garden into a stratified index of Iranian identity. It is art that not only remembers but acts—its pools reflecting shifting dynastic skies while its qanat flows unchanged.