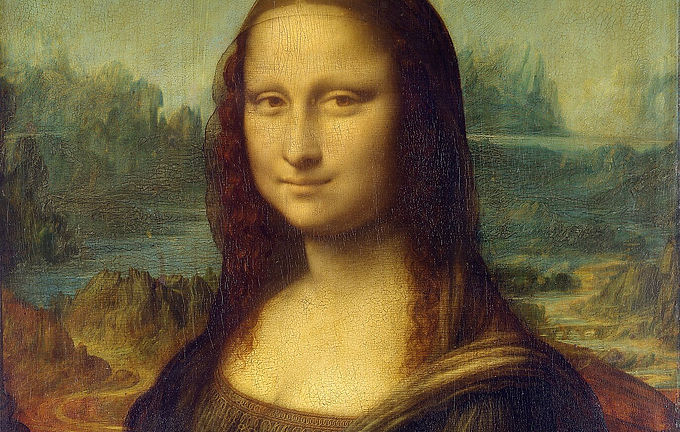

Leonardo da Vinci – Mona Lisa

c. 1503–1506

Theme: Enigma, sfumato, eternal feminine

Visual: A seated woman, turned slightly toward the viewer, hands folded, with an ambiguous smile and distant, dreamlike landscape in the background

Thinking Through Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)’s Philosophy on Art Essence

The Mona Lisa is not a portrait. It is a mask worn by the cosmos. In her, Nietzsche would see not a woman, but the personification of the Apollonian veil—crafted with such precision and depth that it becomes impenetrable. She is still, serene, composed—but beneath her sfumato lies the eternal flux.

What makes her Dionysian is precisely this: she withholds. She does not confess. She offers a gesture, a smile, a presence—but never a meaning. For Nietzsche, she is the opposite of the Christian icon. The Pantocrator commands. Mona Lisa seduces. She haunts. She provokes interpretation, then floats above it, untouched.

In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche says the Greeks created gods not to teach virtue, but to make life bearable. Mona Lisa is such a god—a mask we give to Becoming so that it does not devour us whole. She is an Apollonian dream, but one that gestures toward Dionysus. She shows us form, but whispers of formlessness.

Her smile is key. It is not joy. It is not sadness. It is ambiguity made flesh. Nietzsche would see in it the same smile as Ariadne, the eternal feminine companion of Dionysus. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Dionysus whispers to Ariadne, “Must we not all be dancers?” And she, too, smiles—not in answer, but in complicity. The Mona Lisa smiles in the knowledge that she knows more than you ever will.

She is neither Madonna nor courtesan. She is the collapse of such distinctions. And this is deeply Nietzschean. For what is modern man, if not one who lives beyond morality, in a world where categories falter? The Mona Lisa does not offer truth. She offers the eternal return of mystery. And yet she is rendered with scientific precision—da Vinci’s anatomical studies, his chiaroscuro, his atmospheric perspective. The Apollonian discipline is absolute.

But the result is not clarity—it is obscurity. This is the Apollonian used not to reveal, but to veil more perfectly.

And the background? It spirals, unfolds, a dreamscape of twisting paths, shifting rivers, primeval lands. Nietzsche would call it the face of Becoming itself—a landscape of pre-consciousness, of earth in its mythic phase. Mona Lisa sits before this abyssal flux, untouched. She is the still point in the whirlwind—but only apparently. Her stillness is a surface tension over the void.

Nietzsche’s eternal return asks: would you live this life again and again? Mona Lisa has already answered. She has sat here for 500 years, saying yes to every gaze, every interpretation, every failure to define her. And still she smiles. Not because she is divine—but because she is eternally reborn through vision.

She is the Nietzschean Überfrau—not heroic in strength, but in enigma. Not virtuous, not evil, but beyond moral classification. A woman who cannot be captured, only confronted. And in confronting her, we confront the limits of reason, the seduction of surface, the power of illusion.

Thus, Nietzsche would say: Mona Lisa is not a symbol. She is a Dionysian oracle wrapped in Apollonian skin.

“Do not ask what she means. Ask what she demands of you. And then, if you are worthy, smile back.”