Appalachian Spring

1944

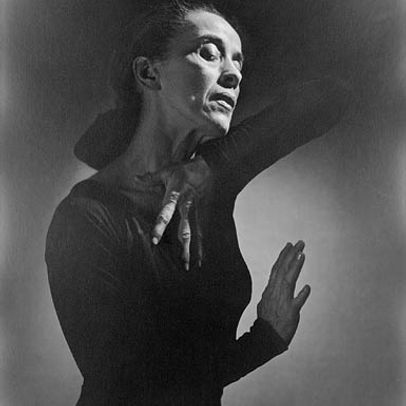

Choreography: Martha Graham

Music: Aaron Copland

Context: A ballet about a pioneer couple building a new life in rural Pennsylvania. Emphasizing frontier ideals, the choreography is often interpreted as a celebration of American resilience, simplicity, and spiritual optimism during World War II.

Thinking Through Michel Foucault (1926-1984)’s Philosophy on the Art Essence

Appalachian Spring is often viewed as a heartfelt tribute to American pioneer spirit, modest faith, and the quiet strength of women. But through Foucault’s lens, this ballet becomes a ritual of national subject-formation, where movement functions not merely as expression but as a biopolitical diagram of morality, space, and domestic futurity.

Unlike the spectral sylphs or mythic firebirds of earlier ballets, Graham’s dancers are emphatically human, earthbound, and angular. They move with intentional restraint, as if each gesture were carved from ethical necessity. Foucault would recognize this immediately as a mode of aestheticized governance—a choreography of the self that arises not from transcendent ideals, but from national pedagogy.

This ballet does not depict freedom in the abstract. It depicts freedom as Protestant effort: the kind that builds houses, marries, raises children, and prays with modest intensity. The physical vocabulary is clear and linear—wide stances, bent knees, spirals—and reflects what Foucault in The Use of Pleasure called a moralized body: a body disciplined through spatial regularity, emotional moderation, and measured visibility.

The central female figure, “The Bride,” is not ethereal like Odette or Nikiya. She is rooted, public, and narratively centered—yet her power lies in her acceptance of gendered responsibility. Foucault might say she embodies a subject of ethical obedience, shaped not through punishment, but through ritualized self-alignment with virtue.

The preacher figure is equally revealing. He is not authoritarian, but authoritative. He choreographs through gesture and presence, not coercion. This is a form of pastoral power—a leadership that knows, guides, and normalizes, rather than commands. It exemplifies Foucault’s idea of modern power as “conducting conduct”—governing not through force but through inwardly adopted disciplines.

The staging is stark, architectural—no ornate sets, no mythical forests. Just white beams, a rocking chair, and open space. This minimalist aesthetic is not accidental; it mirrors modernist truth-telling, the Puritan refusal of ornament. In The Order of Things, Foucault discusses how the Classical episteme seeks knowledge through clarity and classification. Appalachian Spring is not classical, but it maintains that impulse: it orders the American body within an empty frame, choreographing duty, faith, and heterosexual futurity in plain view.

The music—Copland’s score, with its open intervals and folk motifs—does not offer transcendence but expansion. Its spatiality is horizontal, not vertical. It maps the ideal landscape of settler progress, where land is both moral terrain and historical blank slate.

And this brings us to perhaps Foucault’s sharpest insight: the frontier itself as disciplinary myth. The ballet does not question the violence of colonization; it erases it through form. The open plains are unoccupied, the future unwritten. The couple, the preacher, the townspeople—these are not just roles; they are ritual affirmations of settler innocence, performed through a movement language that renders structural power invisible by naturalizing it as simplicity.

In sum, Appalachian Spring is not simply American—it is the aesthetic of American self-justification. Its beauty is sincere, but its structure is deeply ideological. It teaches us not just how to move, but how to inhabit national myth, how to be a good citizen through measured gesture, heterosexual union, and spiritual endurance.

This is not a ballet of freedom.

It is a ballet of governed optimism.