Seneca – Thyestes

1st Century CE

Theme: Dark psychological horror, revenge, and the rupture of cosmic and moral order.

Thinking Through Michel Foucault (1926-1984)’s Philosophy on the Art Essence

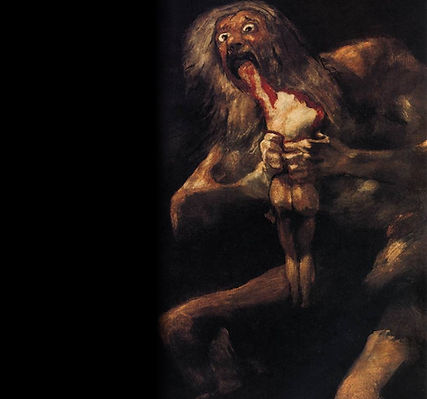

In Seneca’s Thyestes, the stage becomes a philosophical abyss—an unsettling theatre of cruelty where power is unmoored from law and virtue, and where the subject's self-care is obliterated by the excess of transgressive desire. Interpreted through Foucault’s The Use of Pleasure and The Care of the Self, Thyestes dramatizes the implosion of classical ethics and the destruction of the self through a refusal of all limits—ethical, cosmic, or bodily.

Foucault traced ancient Greco-Roman ethics as a relation to the self governed by askēsis—a cultivation of moderation and self-restraint, where power over others was preceded by power over oneself. In Thyestes, Atreus represents the radical inverse: a sovereign whose pleasure is defined not through restraint, but by the obliteration of all self-governance and the annihilation of the Other (his brother Thyestes) through acts of ultimate taboo—fratricide, cannibalism, and deception.

This is not simply a horror tale; it is an archetype of Foucauldian unsubjectivation. In place of the ethical subject formed through practices of self-care, Thyestes offers a descent into the pure will to power, where Atreus fashions his own subjectivity as a god-like judge of fate. Foucault’s idea that “the self is not given to us, it is produced through technologies of the self” is shown here in tragic negative. Atreus creates a monstrous version of the self through a perverse ‘technology’—using dramaturgy itself (staged murder, performance of innocence, orchestration of horror) as a weapon against kinship and cosmos.

Moreover, the play’s preoccupation with vision—the unseen banquet of horror, the slow revelation of crimes—invokes Foucault’s critique of visibility and surveillance. Here, knowledge is poison, not liberation. The spectators are voyeurs to a crime whose full dimensions can never be grasped, much like Foucault’s analysis of how modern power functions by making subjects visible yet unknowable within disciplinary regimes.

Finally, the tragic horror of Thyestes is intensified by its refusal to offer catharsis. It suspends moral closure, leaving the audience in a perpetual ethical vertigo. Foucault might argue that this unresolved violence is symptomatic of a moment when no practice of the self can rescue the subject from the abyss of history.