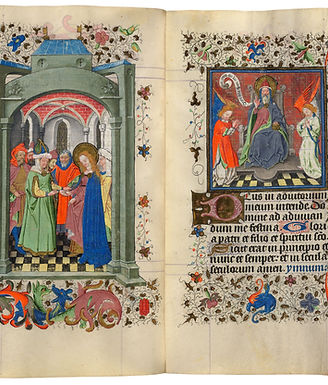

Hours of Catherine of Cleves (Netherlands)

1440s

One of the most richly illuminated Books of Hours in existence, created for Catherine of Cleves, Duchess of Guelders. It features more than 150 miniatures, intricate trompe l’oeil borders, and profound religious iconography, blending Netherlandish realism with imaginative symbolism.

Thinking Through Michel Foucault (1926-1984)’s Philosophy on the Art Essence

The Hours of Catherine of Cleves operates as a masterful interplay of private devotion, aesthetic self-fashioning, and disciplinary technologies of ethical selfhood, rendered in material form. At once deeply personal and extravagantly opulent, it embodies the late medieval transition from the monastic collective to the aristocratic interior—a shift that Foucault interprets as crucial in the formation of subjective ethical governance.

While appearing as a devotional object, this Book of Hours is best understood as what Foucault terms a “technology of the self”: a structured aid through which the individual actively transforms their soul and comportment via self-regulated practices. It guides Catherine not toward the moral surveillance of confession, but toward aesthetic ethical cultivation—the careful organization of time, emotion, and thought according to sacred rhythms.

The profusion of trompe l’oeil frames and everyday objects—bones, fish, coins, candles—are not merely decorative. They illustrate the spatialization of thought: reminders of vanitas, spiritual vigilance, and mortality. In Foucault’s framing, these objects become signs in the cultivation of a vigilant soul: part of an aesthetic pedagogy of inner life, where ethical awareness arises from material prompts that link the visible world to unseen truths.

Catherine, an aristocratic woman in a patriarchal religious world, is offered not a passive space of piety, but a powerful role as curator of her own salvation. The manuscript is her ethical workshop, within which she carves out a daily liturgical rhythm that Foucault might call epimeleia heautou—the lifelong practice of attending to oneself not through shame, but through beauty, time, and meditation.

Foucault’s insistence that the care of the self involves the freedom to shape the soul through aesthetic means resonates deeply with this manuscript. Its abundance of scenes—harsh martyrdoms, radiant Annunciations, tender Pietàs—serve not to terrorize, but to exercise the soul in sensation, memory, and empathy. They are visual asceses, a soft discipline of becoming.