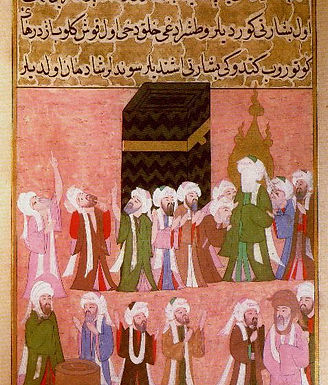

Siyer-i Nebi (Life of the Prophet Muhammad)

Ottoman Empire, 16th century – Illuminated epic of the Prophet’s life in lavish miniatures

Thinking Through Michel Foucault (1926-1984)’s Philosophy on the Art Essence

The Siyer-i Nebi is not merely a devotional narrative or historical record—it is a performative archive of sacred subjectivity and visual ethics. Through Foucault’s lens, particularly his focus on technologies of the self, this manuscript emerges as a mechanism for spiritual individuation and the care of one’s soul through mediated vision. Here, art does not reflect power in a coercive mode—it invites transformation through modeled behavior, affective resonance, and a beautified encounter with the Prophet’s life.

Foucault emphasizes that in Greco-Roman and early Christian cultures, ethics was deeply tied to aesthetics—the shaping of one’s soul through stylized living. The Siyer-i Nebi, produced under the patronage of Ottoman sultans, functions in a similar mode. Its narrative and image structure transform the Prophet into an ethopoetic mirror—a template for the self, where the reader is not just informed but re-formed through the rhythms of reverence. The manuscript’s visual codes—its golden halos, restrained facial gestures, and illuminated settings—are not just iconographic conventions, but technologies of presence and discretion, cultivating pious affect and ethical mimesis.

As Foucault argued, power is not merely repressive—it is productive. In this case, the manuscript becomes a site where Islamic subjectivity is generated through aesthetic mediation. It marks a pedagogical shift from mere instruction to formation of being. The Prophet is made proximate through image, yet distanced through abstraction—a Foucauldian dialectic of presence and invisibility that encourages a contemplative, regulated self.

Moreover, this manuscript is a governmental tool in the Foucauldian sense: the sultanic patronage links religious devotion with imperial sovereignty. The Prophet’s image is politically de-figured—faceless—but the haloed form and rich garments subtly align divine charisma with Ottoman authority. In this way, the Siyer-i Nebi functions as both a manual of ethical life and a visual strategy for legitimation—enfolding political theology into manuscript aesthetics.